Insight Business management

Knowledge creation and management within organisations

IKE fellow Andrew Constable, MBA, discusses the types of knowledge within a case organisation and mechanisms to abstract this knowledge to drive innovation in account management teams.

Organisational knowledge is a key ingredient in the core capabilities of an organisation (Grant, 1996), although there is a limited understanding of the process of knowledge creation and management.

Within organisations, the importance of knowledge is generally discussed openly and there are multiple programmes afoot to enhance the process of knowledge flow. This is where the problems with interpreting the definition of knowledge are evident.

Knowledge flow within the context of many organisations is focused on internal marketing practices of sharing the organisation’s products to enhance commercial growth, therefore exposing the product mix to clients. Little attention is applied to the flow and creation of knowledge within teams that can help develop sustainable innovation (Christensen, 1997). The knowledge within teams therefore goes underutilised from an innovation perspective, leading to organisations becoming stagnant.

What are the different types of knowledge?

The definition of knowledge is ‘justified true belief’ (Nonaka and Takeuchi, 1995). This definition fails to outline the dynamic and humanistic dimensions of knowledge creation, as this is a social process that is linked to a particular space and time (Nonaka and Takeuchi, 1995). This contextual element is often forgotten about, but as boundaries of knowledge are built around a specific context, they allow for shared meaning to be achieved. This shared meaning is called Ba (Nonaka and Takeuchi, 1995) and is vital for knowledge flow.

The boundaries within the case organisation were the account management function and developed into a community of practice (Nonaka and Takeuchi, 1995), whereby this context could be exploited.

Within the initiative, the theory of knowledge follows a western epistemology of knowledge based around rationalism, which is defined as knowledge obtained deductively by reasoning and appealing to mental constructs such as concepts and models (Nonaka and Takeuchi, 1995).

This is in contrast to the empiricism (Carnap, 1991) approach, which is built around sensory experiences. During studies in Japan, Nonaka and Takeuchi based their understanding on this epistemology.

“

Tacit knowledge is built around action, routines, ideas and emotions, and hard to communicate as it’s something we do without thinking."

The process of knowledge transfer, according to Nonaka and Takeuchi (1995), contains two types of knowledge. Firstly, explicit knowledge, which is expressed in a formal manner and is transmitted and stored in tangible form. Within the case organisation, explicit forms such as operational processes are codified to the client account and outline the duties that are to be performed.

The second form of knowledge is tacit, which is more personal and harder to formalise. Tacit knowledge is built around action, routines, ideas and emotions (Toyama, R. et al, 2000). It is hard to communicate as it’s something we do without thinking. This type of knowledge is fundamental to developing sustainable innovation (Christensen, 1997) within the account management function and the SECI model (Nonaka and Takeuchi, 1995) is central to this process.

It is important to recognise that we need both tacit and explicit knowledge to give meaning to the knowledge creation process, as knowledge is created through interactions between tacit and explicit knowledge, rather than from tacit or explicit knowledge alone (Toyama, R. et al, 2000).

The SECI model

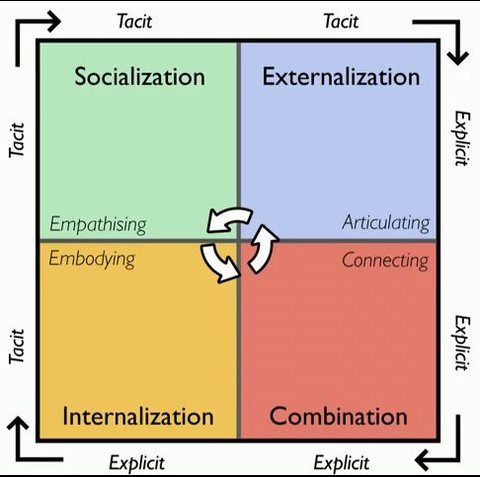

One conduit for abstracting knowledge is the SECI model (Nonaka and Takeuchi, 1995), which is based on the foundation of Ba. It’s important that this model is used in an iterative fashion, whereby we spiral through the different stages codifying the forms of knowledge.

During the initiative within the case organisation, certain elements became more pronounced. For example, during the socialisation stage, a number of the operational managers pulled in intra-firm information by crossing the account boundaries and creating discourse or ‘water cooler moments’ with their colleagues. This allowed intra-firm best practice to be highlighted and implemented into the knowledge spiral for application.

It is important to consider the associated elements of this process as the SECI model is just that, a model. Without taking a holistic view, the application of this will not be successful. It was clear that we must understand elements such as the culture of the organisation, the social structure of the team and how their jobs are designed.

The SECI model (Nonaka and Takeuchi, 1995)

It was clear during the early stages of the cycles of inquiry that a consideration of the organisational culture was imperative. The SECI model wouldn’t be successful if the current culture is not conducive to sharing ideas.

The theory of organisational culture is important and was based on two metrics. Using the model of organisational culture (Deal and Kennedy, 1982), the case organisation at a corporate level operates a quick feedback, high-risk environment. This tough guy, macho culture (Deal and Kennedy, 1982) creates a highly political environment with associated conflict.

This tends to apply short-term measures, which have suppressed risk taking. The risk of failure and reprimand created a low trust environment, leading to individuals viewing the organisation breaking the psychological contract (Herriot, 1992) between the organisation and the individual.

As Nonaka and Takeuchi (1995) state, knowledge cannot be created without the dimension of care, in the respect of mutual trust, empathy, access to help, and a lenience in judgement.