History Innovation

Range and vision: science meets engineering to spark innovation

IKE fellow Richard Barr shares the story of a scientist and an engineer who joined forces to create world-changing innovation in the early 20th century.

When it comes to chemists and other highly trained science-based personnel in industry, I believe engineering employers in the UK have not yet learned to take full advantage of the facilities that are available for securing personnel of sound scientific training. However, the appliance of science in engineering companies remains every bit as important as it was at the beginning of the 20th Century during the industrial revolution.

So why do we still have a divide between academic science and the engineering industries?

I guess that of the many complexities in a multi-functioning society, one is the ability to communicate to different stakeholders such as industry, government and educational. In-depth explanations, fact-based descriptions and the ability to give a meticulously scientific account will ensure the correct discussion is had towards achieving the correct execution. Of course, any assessment of these complexities is not intended as criticism or judgement, but I believe that the link across these three faculties is crucial for success.

One example demonstrating this is the story of my great-grandfather, Archibald Barr, and his business partner William Stroud, who both became considerable influences on my career. The creation of their company, Barr & Stroud, was a world-changing collaboration between an engineer and a scientist that that lead to more than 100 inventions between them, and more than 400 for the company.

The story of Barr & Stroud

Barr and Stroud had been associated with each other from 1888 when they were both, respectively, Professors of engineering and physics at the Yorkshire College (now the University of Leeds).

Barr had studied engineering at the University of Glasgow, where he later became Regius Professor of civil engineering and mechanics. During his study time in the 1870s he served an apprenticeship as a mechanical engineer. At the time, the department of civil and mechanical engineering's famous 'sandwich courses' required students to spend just six months at university on course work, and the other six months in local industry to acquire practical experience.

He then spent several years working as an assistant to his Professor, James Thomson – brother of Sir William Thomson (later Lord Kelvin), a professor of natural science at Glasgow University who developed the Kelvin scale of temperature measurement and was a noted inventor of scientific and electrical instruments. Thomson and Barr often helped Sir William with the practical work of designing his inventions, and through this my great-grandfather was exposed to the potentially highly lucrative application of scientific invention to industrial enterprise.

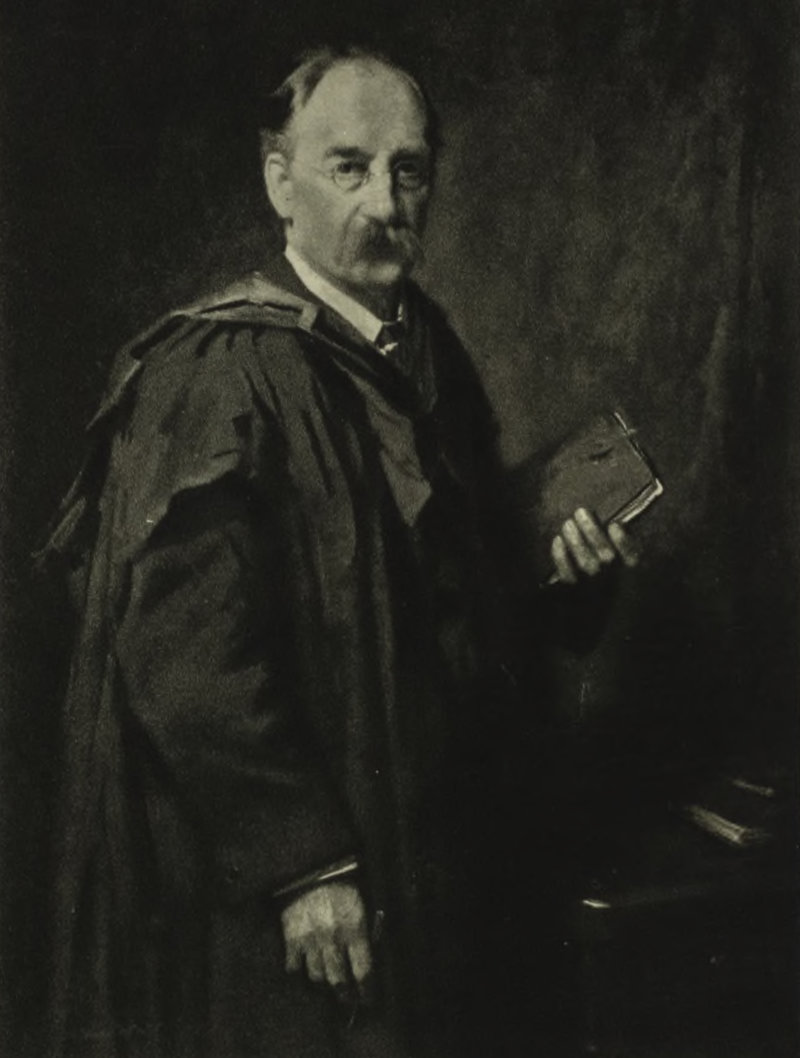

Archibald Barr, one of the founders of Barr & Stroud.

His business partner, William Stroud studied for a BSc in chemistry, followed by a double-first in maths and natural science from Balliol College, Oxford. Due to his reputation as one of the most promising scientists of his generation, he was awarded the physics chair at the Yorkshire College of Science aged only 25.

The company they formed, Barr & Stroud, was a pioneering Glasgow optical engineering firm. It supplied rangefinders to nearly all of the world's navies, and also manufactured smaller, portable instruments which were adopted by the British, French, and other European armies. Barr, who was the senior partner and the head of the design team in Glasgow, remained chairman of Barr & Stroud until his death.

The firm played a leading role in the development of modern optics, including rangefinders, periscopes and binoculars, for the Royal Navy and other branches of British Armed Forces during the 20th century. The company’s non-military arm made motor-cycle engines, cinematographs, vacuum chambers, optophones, and medical equipment such as photocoagulators and electronic filters, some of which were used by the BBC.

Barr & Stroud developed rangefinders for the Royal Navy. Image courtesy of the Dreadnought Project.

A recipe for innovation that stood the test of time

It was Barr's idea that he and Stroud should turn their hands to the invention of scientific instruments, marrying his flair for engineering design to Stroud's talents for applying theoretical scientific knowledge to invention. Making this move more than 100 years ago, he showed great foresight in his approach to combining the two disciplines of science and engineering into a successful and highly innovative company.

His views on employing individuals with scientific training in an engineering enterprises such as the one he set up with Stroud, and on the importance of co-operation between science and engineering, were made clear in a speech he gave in 1906.

“

With reference to chemists and other highly-trained assistants in industry, engineering employers in this country have not yet learned to take full advantage of the facilities that are available for securing men of sound scientific training. I may be permitted to say that in my own firm we have found such men indispensable for the development of work in new lines, and we seldom – I may say never – appoint a man to a responsible job, even in the supervision of purely workshop work, who has not had a sound and extensive course of scientific training.”

He also demonstrated a very modern and forward-thinking attitude towards applied sciences education, saying:

“

I am convinced that one of the worst things a man who was going to devote his life to practical work could do was to spend too much time in any scholastic institution. The best training in applied science could only be got by a combination of scientific study in a university or college and service in a works, and the more intimately these two sides of his training were associated the better. The teacher and the research student should both be in intimate contact with the condition and requirements of the industry to which their work had reference.”

Barr and Stroud’s recipe for success – bringing together great minds from both science and engineering to spark world-changing innovation – still holds true to this day, more than 100 years after they set up their pioneering enterprise.